HEADSTARTING DIAMONDBACK TERRAPINS

The diamondback terrapin, Malaclemys terrapin, is the only turtle in the world exclusively adapted to life in brackish-water coastal marshes. It has an extraordinary range which extends several thousand miles long, from New England to somewhere in Texas, yet is only a few miles wide, depending on the coastal wetlands. The northern subspecies is found from Massachusetts to Virginia.

Diamondback terrapins found in New Jersey show a wide variety of colors

and patterns in both shells and skin. Their shells range from pale yellow-green

to nearly coal black. Their beautiful skin can be a uniform color or display

spots, streaks, or splotches. The colors and markings do not distinguish

males from females, however. Female terrapins mature at six to nine inches

long. Males rarely exceed five inches in length but their tails are much

longer and thicker.

|

|

|

| Note the difference between individual ten-month-old hatchlings. | Diamondback terrapins vary widely in shell and skin pattern and color. | Ten-month-old hatchlings bask in their tank at Stockton's terrapin farm. |

Terrapins hibernate during winter months. When they emerge, these broad-spectrum

carnivores spend most of their active lives swimming and foraging in the

intertidal zone. They feed on mollusks, fiddler crabs, and occasionally

small fish. Bony plates on their upper and lower mandibles enable them

to crush mollusk shells.

|

An adult male diamondback terrapin. Note the moustache-like prominent upper mandible--a feature of all adult diamondback terrapins. |

Only females leave the aquatic environment. They do this in May, June and July to dig a nest and lay their eggs above the high tide. Unlike most other turtles, terrapins nest both day and night. Females may lay two clutches of between 8 and 12 eggs each season. These nests, preferrably buried in a sand dune, are often predated by raccoons, foxes, and others. Developers, landscapers and gardeners often inadvertently disturb terrapin nests in coastal towns.

It is the female terrapin's search for the ideal nest site above the

high-tide line that puts her in harm's way. As barrier island dunes have

been destroyed by development, the remaining suitable sites require terrapins

to cross highways busy with summer traffic. Hundreds of female terrapins

are killed each year in Cape May County alone.

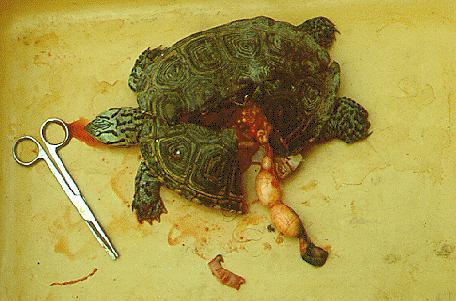

It is with the still-viable eggs of the road-killed

females that the terrapin conservation project begins. Interns and volunteers

from the Wetlands Institute

in Stone Harbor patrol major roadways in Cape May County during nesting

season. Their mission is to collect road-killed females before mammal and

bird scavengers can get to the eggs or the hot summer sun can ruin them.

The dead females are brought back to the Wetlands to have an "egg-ectomy"

performed. Broken eggs are counted as well as viable eggs; organ and tissue

samples may be taken for other research.

|

|

Each clutch is numbered and the location, date, time, weather conditions, and other data in reference to the recovery of the terrapin carcass is noted. The interns work in teams to remove, spray clean, and place the eggs. Plastic shoe box-like containers with vermiculite spread in the bottom hold the eggs as they are swiftly and carefully transported to the science lab at The Richard Stockton College of New Jersey. Extreme care is used because, at this point, the eggs are extremely vulnerable to high temperatures, shaking, or drying out.

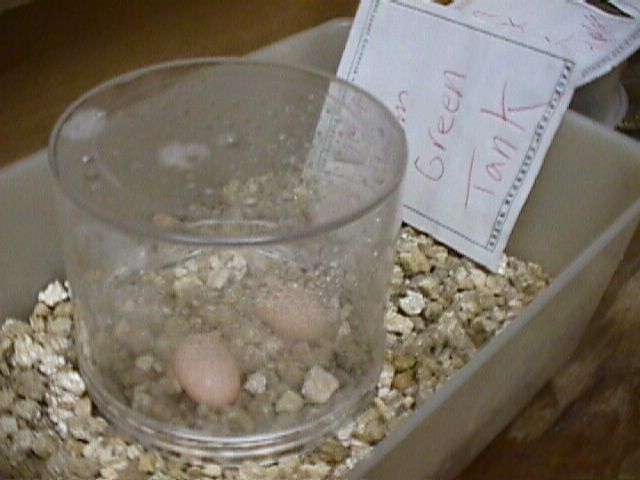

At the College, Dr. Rosalind

Herlands places the eggs in sterile vermiculite which is kept moist

with distilled water. The clutch numbers are indicated on the various plastic

containers that can hold a total of 30 eggs. The artificial nests are then

placed in the lab's convection incubators where they will be tended daily

and checked for fungal or bacterial infections until they hatch approximately

7 to 10 weeks later. When the incubators are full, additional nests are

placed in environmental chambers but, generally, there is a lower hatch

rate from those nests.

|

|

|

| Diamondback terrapin eggs in their artificial nest beside a jar of sea turtle eggs. | Monitoring the progress of terrapin eggs in vermiculite. An arrow on the side of the plastic container helps keep track of the clutches within. | Dr. Herlands explains the incubation stage of the terrapin conservation project to Wetlands Institute interns in front of Stockton's new convection incubators. |

Terrapins, like other turtles, have temperature-dependent

sexual determination. The incubation temperature will determine the

sex of the hatchling. Incubation temperatures of 30-32° C will produce

females; 24-28° C will produce only males. So, it would seem clear

that to replace the hundreds of females lost each season, we should incubate

at higher temperatures. However, Dr. Herlands has discovered a correlation

between higher temperatures and scute anomalies, or shell irregularities.

And, after all, our primary goal in conservation is to return healthy terrapins

to the wild. After a decade of experience, the Stockton terrapin conservation

project can now boast a 40% hatching rate. In 1999, more than 250 terrapins

that were hatched from collected eggs were released.

After the quarter-sized hatchlings emerge from their shells in their

artificial nests, they spend approximately one week in damp vermiculite

while their yolk sacks are absorbed into their bodies. After this time,

they will be placed in tanks of shallow water for a short time until they

are transferred to tanks in the animal lab's terrapin farm that will be

their home for the next ten months

.

|

|

|

| Hatching diamondback terrapins in their vermiculite nest. | The clutch identification number, 26,

is clearly visible on the shells of these hatching terrapins. |

A newly-hatched diamondback terrapin ready to be moved from its artificial nest. |

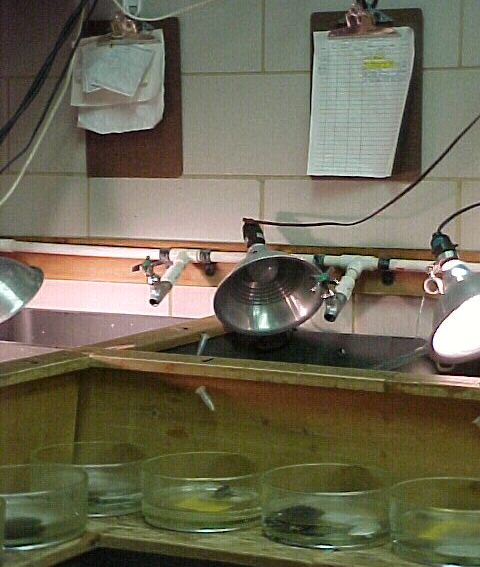

The tanks are actually old lab sinks arranged side-by-side. A huge, 155-gallon holding tank stands elevated in a corner of the room keeping salty water at room temperature. A pipe leads from the storage tank to each individual terrapin tank, each with its own faucet. The water is mixed with parts of Super Salt Concentrate and dry salt. While spending the winter in this briny mix, the terrapin hatchlings will enjoy warm temperatures and 12 hours of light each day. In the room that is the heart of the terrapin farm, the temperature is kept at about 80° F and should never drop below 60° F.

These conditions encourage them to eat almost constantly and so to gain

weight, grow, and develop hard shells. This growth is essential to ensure

that when they are released, they will be too large for gulls and other

predators. They are fed a combination of dried foods daily and chopped

fish once each week. John Rokita

of Stockton's animal science lab has adjusted the "recipe" over the years

always with the goal of providing the most nutritious diet as economically

as possible.

|

|

|

| John Rokita stands in front of the salt-water holding tank in the terrapin room at Stockton. | The tanks for raising hatchlings, finger bowls hold injured or slow-growing hatchlings, and charts that are the equipment of the terrapin farm. | The young terrapins are fed three kinds of dry food daily in addition to chopped fish once each week. |

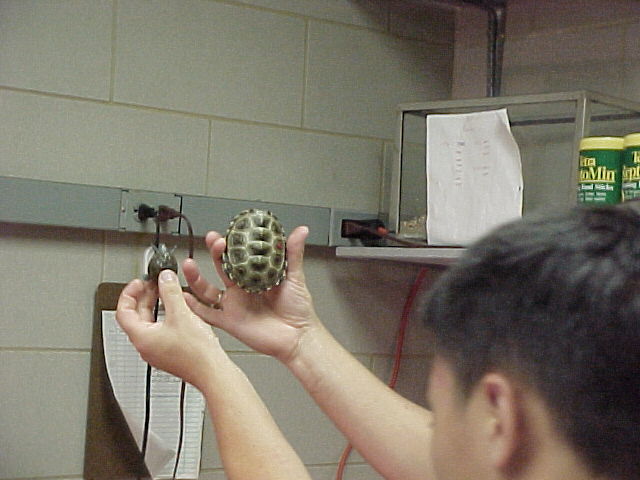

As the hatchlings grow, they are fed more frequently. More frequent

feedings means the water and tubs must be cleaned more often. The youngsters'

growth is monitored and they are separated by size, if necessary, to maintain

a "balance of power" in each tank.

The operation of the terrapin farm is a costly and labor-intensive project.

But by the time the young terrapins are released, ten-12 months after hatching,

they have attained the size and weight of three-year-old terrapins in the

wild. That's in impressive head start!

|

|

|

What happens to the terrapins after release is still a mystery. One goal of our terrapin conservation and research is to learn more about the lives of adult diamondback terrapins in the wild. Towards that end, we have been tagging the terrapins just prior to release. A pellet is injected under the skin of one of the terrapins' legs. The pellet provides a unique ID number for the terrapin and is readable by scanner if the terrapin is ever recaptured. The project is able to tag a limited number of terrapins each year due to the expense of the pellet tags.

What we do know is that some of them will meet the same fates as their mothers on busy roads. They could be legally collected from November through March. Or their scavenging nature might lead them into a commercial crab trap.

Dr. Roger Wood of Stockton and the Wetlands

Institute has invented a simple device to keep terrapins out of commercial

crab traps. His Bycatch

Reduction Apparatus (BRA) or Terrapin Excluder Device (TED) has reduced

terrapin drownings by 90% and simultaneously increased the catch of marketable-sized

crabs. The success of this conservation tool lies in convincing crabbers

to use it.

Much remains to be discovered about the lives of adult diamondback terrapins-their individual ranges, breeding habits, genetic variability, life span, etc. Tagging yearlings at release and then recapturing them is one step toward discovery. Collection of organ and tissue samples from terrapin carcasses is another means of collecting data.

The project does allow opportunities to observe live adult terrapins

as well as collecting dead ones. Sometimes adult females are found with

cracked shells or other minor injuries. John Rokita of Stockton has saved

injured adults by providing care and refuge. Veterinarian Dr. Mark Logan,

working with the Wetlands Institute, has wired shells together and sealed

fractures with dental epoxy. The wire will stay with the terrapin forever

but the dental epoxy eventually falls off. The project's research has discovered

that the shells have a remarkable capacity to heal themselves.

|

|

|

| A female diamondback terrapin with a cracked bridge and carapace patched with dental epoxy. | Although this female terrapin will bear scars, her injured shell was already healing when she was found. | These eggs were laid by an injured female terrapin in a swim tank at Stockton's terrapin farm. |

Hopefully, tenacity like this, with a little help from projects like

the cooperative one between The Richard Stockton College and the Wetlands

Institute, will save the northern diamondback terrapin from extirpation

in southern New Jersey.

Terrapin Home | Margaret Simon's Terrapin Page | Stockton Home