|

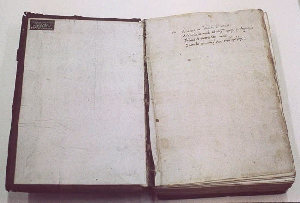

Study of the scribal style, paper, and binding identify

Manuscript Latin 13 as a text of Italian origin, copied and

bound sometime around 1500. It was not a volume of great

worth: there is no illumination, no rubrication, and the binding

is not gilt. But neither is this a poor man's book. It has been

carefully copied and skillfully bound. It was meant to record

and protect its contents, to provide a suitably artistic cover, and

to be affordable. The identity of the binder is not known.

|

Close examination of Ms. Latin 13 reveals that some marginal notations were cut away as the binder trimmed the edges, leading to a fourth, and perhaps the most likely scenario. The manuscript may have lain for some time in sheets (or perhaps a temporary binding) during which time it was studied and annotated; some time later it was bound. In any case the gatherings that make up this paper manuscript, four cosmographies in Latin translation, came into the hands of a skilled binder. There are thirty-four gatherings, generally of five interleaved sheets each--gatherings in 10s.2 The binder's first task was to order the gatherings so that pagination was correct. He next prepared front and back endsheets of appropriate size.

The style of endsheet construction used here was common throughout the period. A single sheet of paper was folded once, making a bifolium. The joint edge of the resulting bifolium was folded again so that there was a narrow stub (approx. 8 mm.) that would be wrapped around the joint of the initial gathering before sewing.

|

The front stub has torn away from the endsheets, but is clearly visible in this photograph showing the bottom half of the open text.Once the endsheets were prepared and fitted around the gatherings, the spine of the textblock was aligned. At this time sewing holes may have been pricked individually in each gathering. Evidence in other volumes suggests that sewing holes were produced by making light knife cuts across the spine at locations that would be appropriate for the sewing supports and kettle stitches.3 The sewing supports are only roughly equidistant on the spine, with the kettles being placed a bit less than halfway between the textblock ends and the nearest sewing supports. The binder was probably estimating by sight alone.

|

The straps were slit down the middle, at least the width of the spine (again about 43 mm.), so that the sewing could be threaded twice through the center of the strap and wrapped around opposing halves. The lower end of the strap (now a slit strap), which would correspond to the front of the text when bound, was probably affixed to the sewing table with a tack; the upper end, corresponding to the back of the text when bound, was perhaps left free or tied in place to the crossbar of a sewing frame.4

At this point the sewing of the initial gathering, with front endsheets wrapped in place, was begun. Outside of the first gathering the thread, sturdy linen guided by a sewing needle, was sewn through one of the kettle stitch holes to the inside of the gathering. The thread was run along the inside joint to the hole at the first sewing support where it was laced through both the hole and the slit of the sewing support, wrapped around one half of the support, laced between support and gathering, then wrapped around the second half of the support, again through the slit, and back through to the inside of the gathering. The thread ran to the center of the gathering and the procedure was duplicated at the center support, and then again at the third support. Inside the gathering after attachment to the third support, the thread was run along the joint until it was laced out through the needle hole at the kettle stitch and in through the neighboring kettle stitch hole of the second gathering. The sewing pattern now ran in the opposite direction to that used in the first gathering. When the thread ran out the kettle stitch hole in the second gathering, the initial thread end was tied off, then the sewing was threaded into the third gathering. The third gathering, then, was sewn in the direction of the first. The sewing continued, the binder working his way through the textblock, with the kettle stitches linking with the thread of the previous gathering before being threaded into the next. The result was a linking sewing-pattern at the kettle stitches. After working through each of the gatherings, the sewing was tied off after the sewing of the final gathering, which included the wrap-around back endsheets.

After the textblock was completely sewn, the supports were untacked from the sewing table. The textblock was then placed within binding clamps and the edges were trimmed even, either with a binding plow or with an edging knife. The resulting textblock measured 206 mm. in height, 145 mm. in width, and 43 mm. in width. The edges were left undecorated.

|

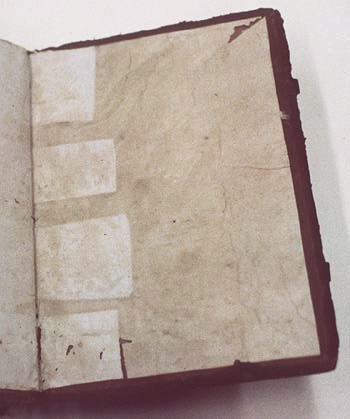

Attention shifted to the spine. Four strips of parchment

(manuscript waste measuring approximately 110 mm. x 40 mm.

each) were pasted over the spine between the supports and at

the top and bottom panels. These transverse spine linings,

overhanging the spine by approx. 30 mm. in the front and 40

mm. in the back, would later be pasted to the interior of the

boards.

Transverse spine linings clearly show beneath the back pastedown.

|

The primary sewing of the endbands used the same sort of linen thread as that used to sew the textblock. The thread was laced inside of the first gathering, out the kettle stitch hole (piercing through the transverse spine lining), and over the endband core. The thread was then wrapped completely around the core in order to obtain a tight winding. Using both ends of the thread, alternately wrapping around the core, lacing one thread end over the other at the textblock edge, and sewing into the gatherings at every other kettle stitch, the primary sewing was completed with a bead on the textblock edge. A secondary sewing was achieved by simply wrapping a green thread around the primary sewing, leaving gaps in the winding so that the color pattern alternated white and green. When the endbands had been completely worked, the core still jutted approx. 20 mm. beyond either side of the textblock. These ends would be laced into the boards.

The textblock was now ready to be secured to the boards. The type of wood used for these boards has not been identified--not enough of the board is visible--but the most commonly used wood seems to have been beech. There was a significant amount of preparation necessary to prepare the boards. First they were cut and planed to the proper size and thickness, with the grain running vertically from top to bottom. The 213 mm. height allows the top and bottom to overhang the textblock by approx. 4 mm. (Binders refer to this overhang as the volume's "square.") The 145 mm. width provides negligible overhang at the fore-edge. Each board is approximately 5 mm. thick. After the boards were cut and planed to size, the boards were bevelled, probably to improve their ease of use and to minimize their bulky appearance. The inside of each board, at the top, bottom, and fore-edge, is bevelled across the width of the board, with the bevel extending inward about 5 mm. The interior spine edge is not bevelled. On the exterior there is a gradual bevel that extends inward 15 mm. from all edges.

Once the boards were bevelled, channels were cut into the exterior side to accommodate both the sewing supports and the endband cores. These channels, approximately 3 mm. deep, were long and wide enough to allow the ends of the supports to be placed snugly within them.6 Three channels for the sewing supports are cut into each board at right angles to the spine edge. The channels for the endband cores are cut diagonally onto the boards, starting at the spine-edge corners.

Common features on wood boards from this period are shallow rectangular recesses cut into the exterior of the upper board, at the fore-edge, to accommodate the strap anchors. This volume is unusual, but not unique, in not making use of such recesses.

Once prepared, the boards were fitted over the textblock, with sewing supports and endband cores placed into the appropriate channels. If any supports were too long they were trimmed to fit the channels. Because the covering leather and pastedowns are intact, the method of securing the ends of the supports cannot be seen. On most volumes with wood boards, however, supports of this sort were secured either with one to three wood pegs or iron nails. Pegs are probable, given the fact that tell-tale rust stains left by nails are not visible.

The forwarding of the volume was now nearly complete. A brownish/red goatskin was first cut to rough size for use as the covering material. The side of the leather to be placed against the boards was then covered with paste as were the exteriors of the boards (and perhaps the spine). The leather was fitted over the spine, smoothed over the boards, and wrapped onto the interior of the boards (reaching anywhere between 10 and 45 mm. onto the inside cover.

|

There was bulging at the

interior corners; this was smoothed by making two diagonal

knife cuts and removing the excess leather. This interior

leather, the turn-in, was also pasted to the board. The entire

volume was then tied up (or placed in a press of some sort)

until the paste was dry.

The cut edge. |

The clasp straps (now mostly wanting) appear to have been made from the same goatskin as that used for the covering. The straps, reaching from the upper cover to the lower, were approx. 16 mm. wide and 2 to 3 mm. thick. The leather of each was folded to a double thickness and may have been wrapped around a paper or parchment center. Since there are no recesses on the board, the straps were simply laced through slits in the covering leather at the fore-edge of the upper board and anchored with two iron nails each. The clasps, now missing, would have been secured to the end of these straps.

|

A trefoil catchplate.The two catchplates, placed at the fore-edge of the lower cover, are made from a sheet of brass that has been cut and stamped into a trefoil shape. Each is secured to the board (over the covering leather) using 3 small brass nails. When the last small nail was tapped through the leather into the board, the binding was complete except for the pastedown which would finally be pasted over the inside board, covering the leather turn-in and any visible nailing and pegging.

|

1. Anthony Hobson states that c. 1510 in Italy "Binding was normally carried out by Booksellers. . . ." see Humanist and Bookbinders, p. 120. In an earlier essay Hobson explains the distinction between binders as booksellers and as stationers: ". . . bookbinding was not an independent trade in Renaissance Italy. It formed part of the function of retailing and was normally carried out by booksellers or stationers. . . . Stationers can be assumed to have been responsible for groups of bindings consisting largely or exclusively of manuscripts, booksellers for those containing a fair proportion of standard books bound for stock." See "Two early sixteenth-century binder's shops in Rome," De libris compactis miscellanea (Bruxelles: Bibliotheca Wittockiana, 1984), p. 98.

2. A gathering in 8s completes the first title; a gathering in 8s completes the second title; a gathering in 6s completes the fourth title, and thus the volume. All other gatherings are in 10s.

3. Several volumes show signs of these knife cuts, visible as short slits that run onto the joint edges at the outside and inside of gatherings, including volumes: 2, 3, and 16.

4. We hope that our narrative does not suggest that Renaissance binding techniques are clearly understood in every detail. That is not the case. The strap here described, for example, may have been slit only after it was affixed to the sewing table. The binder would have guessed at the appropriate slit length and then run his cutting blade upward from a position slightly above the tack. Without detailed contemporary descriptions, we can only suggest possible techniques. An even more glaring lack of knowledge surrounds the sewing table itself. Although sewing frames had been in use in Europe(?) since the eleventh century, it is not clear whether a predecessor to the modern sewing frame was used or whether the volume was simply bound at the edge of a wooden table.

5. The mixing of alum-tawed and leather thongs on this volume may suggest the modest size of the binding establishment. In a larger bindery there could have been several apprentices, one whose responsibilities included maintaining a supply of prepared endband cores (and sewing supports?). In a small shop, without such specialization, the cores might have been prepared as needed. When the time came to sew the second band, if the supply of alumętaw thong was exhausted or misplaced, a leather thong, easily prepared, did just as well. See Albinia de la Mare, "The Shop of a Florentine 'Cartolaio' in 1426," Studi Offerti a Roberto Ridolfi (Firenze: Leo S. Olschki Editore, 1973), pp. 237-48., where de la Mare suggests three as the possible number of workers at a stationer's shop c. 1426. Of course the use of two different core materials can be explained in a variety of ways that have no relation to the size of the shop.

6. Saw cuts clearly evident on other boards (see discussion of volume 16, p. 00) suggest that channels were made by first making two parallels saw cuts of the appropriate length and width and then gouging out the center, probably with a chisel.