The Kennedy Farm

By Raymond Dudo

In 1969, New Jersey’s Department of Higher Education signed Stockton University into existence, and it quickly became a jewel of South Jersey. Some called it “Diamond in the Pines,” and the secluded, natural, newly-discovered feel of the college was poignant among the first classes of students and the first members of administration and faculty. By 1972, Stockton had acquired large tracts of land in the Pomona area of Galloway Township and had begun building a campus. With this new campus came an innovative concept of what higher education could be. Experimental classes, faculty advisors who were true friends, and rich untouched South Jersey forests: these were all alluring parts of the Stockton experience.

Recently, local historians have done essential work to prove this narrative false—well, only some of it. Stockton is still proud to explore the best teaching practices and to experiment with them. It still has a caring Stockton Family that is deeply involved with the well-being of students, and its campus is still abudant with spectacular pines, cedars, lakes, and wooded paths. The story these historians are proving false one of nothingness: the myth that, before Stockton, the land was untouched. We now recognize that this land has seen many owners, among them some of the most important members of the community.

I would like to add to the current research regarding our university grounds; therefore, I have compiled the history of forty-five acres of land situated at the corner of Jimmie Leeds Road and Vera King Farris Drive: Lot 887 of the Gloucester Town and Farm Association. We know it as the entrance to Stockton. This land has a fascinating lineage and has changed hands many times in the last one hundred and thirty years. However, its ancestry is mostly tied to one family who owned the parcel for the longest period of time. That family was—and proudly still is—the Kennedy clan.

In 1972 the Department of Higher Education bought sixty-five acres of land for sixty thousand dollars. The land was a farm, owned and operated by Leonard and Fern Kennedy with the help of their children. Rumors say the land was seized in an eminent domain case; however, after pursuing this thread, I found the story to be even more moving. As mentioned earlier, New Jersey signed the documents for a new college in 1969. In that same year, a newly founded Board of Trustees convened on behalf of the new Richard Stockton College. They decided to build their new campus on a large plot of land in Pomona, New Jersey, and underwent the tedious task of purchasing the lots from local farmers and the Township. Their plans were decelerated, though, in a surprising manner. One farmer (i.e., Leonard Kennedy) rejected the state’s offer and preferred his life of growing, packing, and hauling over a check from some state official. Leonard and Fern Kennedy, husband and wife, decided in 1970 they would never sell their farm. Their battle lasted three years. Threats were made on both sides, guns were drawn, but, in the end, the land was sold. First, allow me to share their history.

On April 8, 1939, a young and lavish Long Island woman with an extravagant name, Antoinette Woolf, bought a forty-five-acre farm lot in Galloway Township, New Jersey. The purchase was interesting, considering the land was in bad condition and the single house on the property was not much to speak of. She and her husband Paul had made grand plans with her brother, Leonard Kennedy, to buy this property and make a profit from it in some way. Leonard was a sailor, and before he could see the land, the United States Navy called him to serve in the Second World War. He was sent to the Pacific, and the memories he earned in that sad heat changed him.

When he returned from the gruesome war, Leonard had two goals: hard work and a quiet life. Before he attained those, he found his soon-to-be wife. While on leave, Leonard visited Reading, Pennsylvania, and there he was introduced to a young lady named Fern. He fell for her immediately. She had other thoughts. “I didn’t like him. He was too full of himself,” says Fern in an interview conducted by her granddaughter, Sara Brown. Fern Kennedy, now 94, remembers thinking the young sailor was arrogant. Still, she gave him a chance, and he proved to be a loving, hard-working, and almost never-complaining man.

When Leonard was eventually relieved of his naval duties, he married Fern and the two turned toward Galloway Township. During this interim, Antoinette had sold Lot 887 to their mother Harriet, because Antoinette and Paul Woolf had given up on the idea of a farm—it was more Leonard’s idea than theirs, anyway. Harriet Kennedy (who eventually remarried as Harriet Lore) bought the lot from her daughter for $1 in 1945. When Leonard was ready to take up his life in Galloway, his mother sold Lot 887 to him for $3,100—quite a good turnover for Harriet. On January 1, 1947 Leonard and Fern owned the land where they would build their marriage, raise their children, and make their living.

I was fortunate enough to converse with Darlene McIntire (née Kennedy), eldest daughter of Leonard and Fern. Darlene is one of the seven Kennedy children, and I have spoken to all of her living siblings. Sadly, her brother Lenny and sister Loraine are no longer with us. Their memory lives on in their families, and hopefully in this project.

Darlene told me many stories about her time on the farm in the fifties, sixties, and seventies, yet I also asked her about her parents’ lives. Leonard and Fern came to Galloway without any farming experience. How did they begin? How did they learn? What did they do once they settled on their new forty-five acre lot?

They began a pig farm. There was already a pig farmer named Dilke across the road, and it is possible that he shared his knowledge with the couple. Darlene only confirmed that he was there and that her parents began raising pigs for slaughter during their first year. Paul and Antoinette often visited, and Leonard was not shy to ask his brother-in-law for a hand. The Kennedy’s raised pigs successfully for a short time, but it was a long and arduous process. Between operations at the pig farm, they attended classes held by the local cooperative extension concerning vegetable farming. They learned a great deal and decided to purchase one horse and one plough to try their hands in the soil. By this time, Darlene was already born, and Fern would soon give birth to young Leonard “Lenny” Kennedy. The family started their vegetables by hand, sowing each row of seeds after the senior Leonard and the horse ploughed. Fern Kennedy said it was difficult work, yet she enjoyed it. This might seem strange, considering she was from a heavily populated area of Pennsylvania. Fern had come from the urban side of Reading, and she grew up in a row home. But the change from city streets to farm country made her very happy, forever defining her as a woman of soil and living things.

Soon Leonard and Fern got out of the pig business and focused on vegetables. They did well, and slowly—very slowly—they grew their enterprise. A tractor was purchased, and then a better tractor, and then a planter, followed by a cultivator. By the mid-1950s and the birth of three children (with a fourth on the way), Leonard and Fern had a lovely vegetable farm, bustling with the help of little Darlene and Lenny.

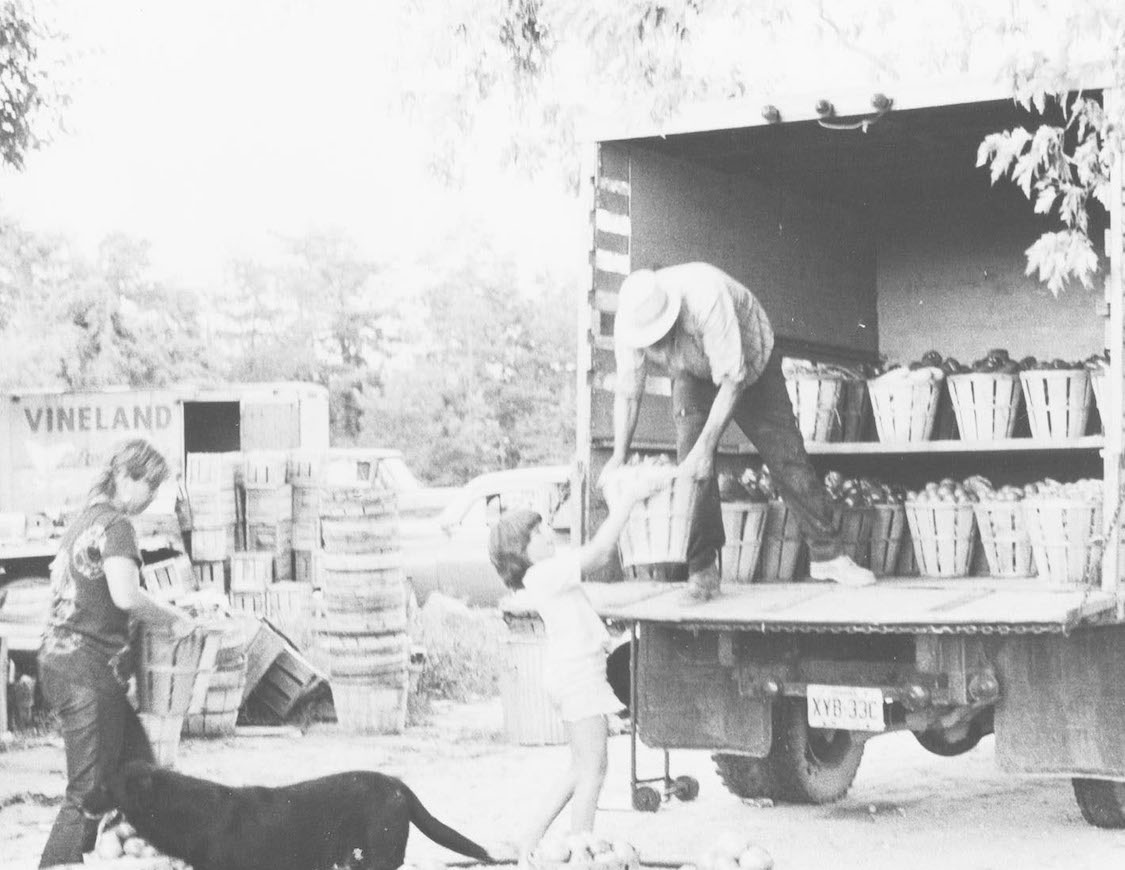

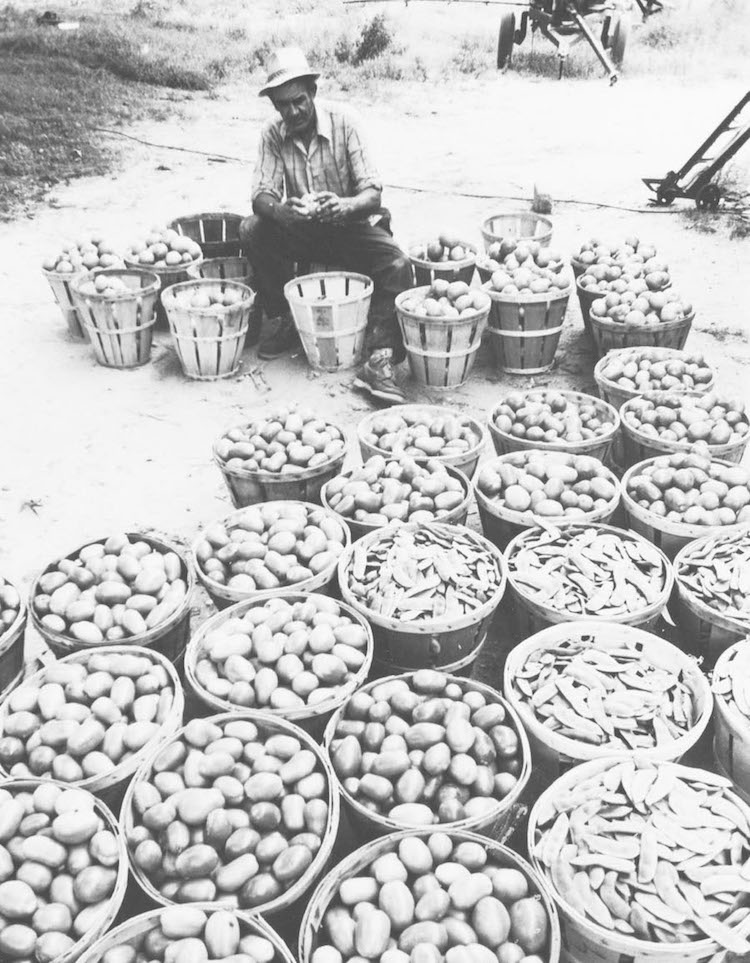

The Kennedys sold their produce at the Atlantic City market, and Leonard transported their goods in his trusted blue truck with a wooden panel bed and storage area. Leonard and Fern worked side-by-side in the field, the greenhouses, and the truck—as long as the children were looked after by one of their eldest. Their tasks included ploughing, leveling, sowing, watering, tending, picking, and sorting, followed by loading the hundreds of baskets of vegetables and fruit into the truck for transport. When Leonard went off to the market, Fern made jams and jellies while caring for the kids. In 1957, the Kennedys were doing so well they bought an additional twenty acres directly behind their lot. For two hundred dollars, they expanded into a sixty-five-acre, successful farm. This lifestyle lasted throughout the fifties and spilled over into the sixties. By 1965, all seven children were born: Darlene, Lenny, Donna, Loraine, Sharon, Lynn, and baby Fern. Darlene remembers these years, and she says they were wonderful. She told me:

It was a good livelihood. We never thought we were deprived, ever! That was our lifestyle. We had plenty to eat; we went places. On Sunday, we would go to Wildwood for the day, or out to Absegami for picnics. And all summer we worked on it, and we would break when it was hot and go to the Port beach to swim. My mom would take us over—that was ritual—then come back later when it cooled off. My dad was a big drive-in movie person. On Saturday nights, us older ones would go to the drive-in in Absecon. He loved movies. And it was just our way! I never remember feeling deprived.

The Kennedys were doing well, and their crops were being sought after at the Atlantic City market and even by large supermarkets like Acme. They had spring crops, summer crops, fall harvest, and winter greenhouses. Darlene told me they worked up until frost. After, Leonard would cut wood to sell on “the island.” He sold wood in Margate, Ventnor, and Atlantic City, and this lasted most of the winter until crops were ready to be sown; his blue truck was always full of something.

When the children heard his old truck returning from the market, they rushed out of the house and began picking. Fern would caution, “You better get out there before your father reaches the house.” The children did just that, running as fast as their legs would allow to “raise lots of tomatoes, and peppers, and eggplants, and lima beans, and string beans, and squash, and cucumbers, and corn: everything. In the Fall, the pumpkins and the fall greens.” Later on, the Kennedys would expand their farm, and add a farm market to their list of accomplishments. They bought a small property in Absecon on the White Horse Pike and opened a farm market there. Kenneth Sooy of the Galloway Historic Society is a local farmer and historian and Darlene’s uncle by marriage. He remembers the market well, but the location always stood out to him most. According to him, “They were right on the way to the shore. They got all the shore traffic. Great location.” The market became young Lenny’s passion and pride, and he began managing it solely. Ken remembers Lenny as a man with a warm and robust presence. Ken claimed with a laugh, “he could sell ice cream in the Arctic.” Lenny became a legend in the Galloway area, and his market was always full of products and people. He kept the market running for the rest of his life.

Working on a farm is hard work, though. Fern Kennedy and Darlene were sure to emphasize this point. Sara Brown asked Fern if she remembers the labor and how it made her feel. Fern replied, , “Well, peaceful. You never forget that. You worked hard but you enjoyed it, and I enjoyed working hard.” Darlene agreed sincerely. Being a farmer from birth, she also had great stories to share from her experiences. I began to understand another interesting facet of living in Galloway Township in the 1960s: the culture shift that occurred in the United States during the mid-twentieth century pervaded every corner of the nation, even a small, isolated farming community like Pomona. Darlene’s parents embodied the pre-shift, and, in many ways, the history of the Kennedys is a story of the unprecedented—and unexpected—change in America. For example, Leonard was a fair man, but he expected work from his children. He was an old farmer in that sense: never hiring extra farmhands to help because he had children to do just that. Darlene remembers her father’s expectations and told me an interesting story about a run-in with the truancy officer.

“When we were heavy with the strawberries, he would make us older ones stay home from school at least one day. But days that he didn’t make us stay home, we had to get up early and we each had to pick a flat before we went to school,” explained Darlene. This practice was regular among farming families in America for years. In some communities, school was even deferred during harvest. By the 1960s, this idea was largely out of fashion, especially on the east coast. Darlene’s sisters and brother were accustomed to this practice, but it came to an end when the truancy officer from Pomona School showed up on the Kennedy Farm. He convinced Leonard not to keep the children home from school, explaining the legality of the situation. Still, the officer did allow the children to finish the day’s work. After that, the Kennedy children would only pick in the early morning and the cool evening during the school year.

When summer came, they were out in the fields planting seeds, picking fruit, and moving irrigation pipes by hand. When Darlene, Lenny, Donna, and Loraine were teenagers, Leonard and Fern thought up a nice way to fairly compensate their children. Leonard said, “I won’t pay you, but here’s what I’ll do: all the squash will be yours. Whatever you make, I’ll give you the money.” The eldest children thought it reasonable and became responsible for the whole squash crop: ploughing, planting, growing, harvesting, and selling. This responsibility would change the children forever and instilled a work ethic that is still present to this day. During my interview, Darlene could not be more grateful for the tiresome work of her youth. She says it taught her and her siblings that “you have to work for what you want. And we ended up teaching our children the same thing. They know about working hard, and they’re teaching their kids the same thing.”

Fern Kennedy remembers delivering these essential lessons, and she still smiles to think her children are passing down the “Kennedy way.” “They all say they never want to farm again, but they enjoyed it, I can see it in the way they talk,” she wisely reported. After speaking with most of the Kennedy children, I can confirm this observation. All of the Kennedys speak about their family farm with an air of heaven: a place non-physical, as memories are, but for which they yearn.

One of my favorite stories involves Darlene’s husband, Jimmy McIntire. James and Darlene began their romance in high school, but he was never allowed to escort her on a night-out. Instead, Leonard insisted the young teenager come visit the house. Little did Jimmy know he was being lured into manual labor by the old farmer. When Jimmy visited, Leonard would yell up the road, “Give me a hand with this,” thus starting a lifelong bond between mentor and apprentice. Jimmy loved farm work from the start, and Darlene remembers her love-interest following her father around the farm, helping in any possible way.

Like Leonard, Jimmy was also called to serve. He was deployed to Vietnam, and like his mentor before him, war changed the man: Jimmy came back to New Jersey with hurtful memories. Leonard put his arm around him and said, “Don’t worry about a thing. You’re gonna work right here on the farm until we figure out what you’re gonna do.” Darlene remembers the poignant scene clearly. The year was 1971. Jimmy worked on the Kennedy Farm for another year, but the days of the farm were numbered. Soon, Stockton College would buy the sixty-five-acre farm, and the Kennedys would depart from Galloway. The lovely moment between two veterans of war did not go unblessed, as Jimmy McIntire received a job at Stockton, where he worked for the rest of his life. Possibly the first veteran in the Stockton Family was a Vietnam Vet who loved the land on which he worked: Jimmy McIntire.

In 1970, a representative for the State of New Jersey arrived on the Kennedy Farm with exciting news for the southern part of the state. A public college had been approved by the Department of Higher Education, and Pomona had been chosen as the site of the campus. The official informed the Kennedys their farm would be a portion of that campus, and he brought an offer for the land. In response, Leonard went inside his home and brought out a counteroffer: a rifle pointed at the official. Leonard waved the barrel towards the road, advising the man which direction he should go. Leonard might as well have been pointing that rifle at the state itself because, after that day, a war was waged between the Kennedy Farm and the State of New Jersey. Leonard and Fern were insulted by the offer brought to them, and Fern remembers the figure being laughable. For three years, they fought City Hall; and for three years, officials tried to approach the house with offers. The fortune of Lot 887 was in a stalemate.

Although they didn’t have Leonard and Fern’s land, the state continued buying the rest of their planned properties. In three years, all the land for the campus was purchased, all except the front sixty-five-acres where the entrance to the campus would be. The Kennedy’s property was on the corner of Jimmie Leeds Road and Louisville Avenue (now Vera King Farris Drive). Those familiar with our campus can still see the Kennedy lot to the right of the main gate. By 1971, construction began down Louisville Road, but the Kennedys held firm. Fern remembers the college being built and the endless line of trucks and men heading into the woods to raise our campus.

Operations at the farm continued, for Leonard and Fern and their seven children had no intention of leaving their home, college or not. By 1972, classes were ready to be held at the Galloway Campus. At that time, the Kennedy’s received their final visit from the state. The Department of Higher Education offered them sixty-thousand dollars for the sixty-five-acres, barns, greenhouses, resources, and house. The officials threatened what would happen to the farm if the Kennedy’s refused this offer. Fern and Leonard were unconvinced. “We turned it down, and they said if we didn’t agree with it, they were going to condemn us and we would have to get out.” If they rejected, all permits and licenses would be revoked, and the Kennedys would never grow or sell another crop in New Jersey. With no options, Fern and Leonard took the money. That is how the Kennedy Farm of Pomona, after twenty-five years of operation and living and growing, came to its conclusion. This sad time was the end of a lifestyle the family had known for over two decades; however, it was not the end of the Kennedys and their influence in the area.

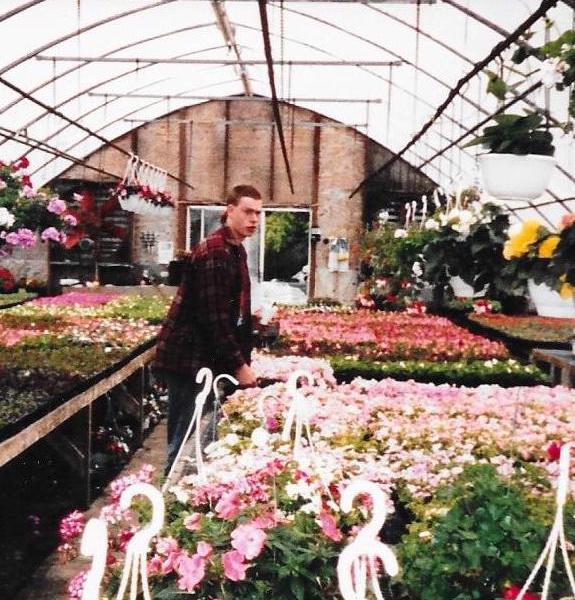

With no farm or home, Leonard and Fern searched South Jersey for a new start. Their son Lenny and his wife had grown the Absecon market to a considerable size, and Leonard decided to follow this model. With their eldest children married or moved, Leonard and Fern brought their youngest children to Estell Manor—a small community made of farmers, the wealthy, and the hiding. Combining the money from the state with a Farm and Home Loan, Leonard and Fern opened the Kennedy Farm and Garden Center on Route 50—a busy highway used by shore enthusiasts to reach Wildwood and Cape May.

The Kennedys began anew, and their dedication to hard work brought them success in their new endeavor. The Kennedy Farm and Garden Center became known as an excellent small greenhouse operation, and the locals respected the seasoned farmers. Leonard and Fern lived in a comfortable house nearby, and they enjoyed life. Each year on October 31st, the Kennedys and their descendants held a huge celebration for Fern’s birthday. Fern Kennedy was then, and still is, a unique woman. Her antics and wit are legendary, and her self-given nickname, “The Devil,” displays a little of her humor. Her children state she was the driving force at the farm market; although Leonard was still deeply involved, Fern took a leading role in Estell Manor.

To keep his new farm market full, Leonard began purchasing produce from the Philadelphia Market. Stephen Brown, husband of the youngest Kennedy daughter named Fern, remembers driving to Philadelphia at 2:00 a.m. with Leonard, and hopping over the fence before the market opened to get the best spot in line. Stephen became very involved with the Farm Market after meeting his wife Fern. The youngest Kennedy children stepped into their older siblings’ shoes at the new market, helping their parents just as the others did. Lynn and Fern Kennedy (now both Lynn and Fern Brown) were vital to the market, and they helped their parents for many years.

At this point, there were three Kennedy markets in operation: the Estell Manor market ran by Leonard and Fern with their daughters Lynn and Fern; the Absecon market flourishing under the management of Lenny; and another market in Leeds Point, operated by eldest daughter Darlene. She and her husband Jimmy continued their lives as farmers because, from adolescence to adulthood, they were always linked to the soil. So, when Stockton bought the old farm, Jimmy suggested they start their own. The Bayside Farm Market in Leeds Point was open for over thirty years owned and operated by Darlene and Jimmy McIntire. Jimmy worked at Stockton and Darlene was a teacher, but their true passion remained. Darlene continued making her mother’s famous jams and jellies, and she remembers never having enough for their market’s shelves. Their big grey barn still stands right by the Oyster Creek Restaurant.

The Kennedy family had grown up and got on living, but their hands never left the soil. The Kennedy Farm and Garden Center stayed vibrant for many years, until the death of Leonard Kennedy in 1990. Fern and her daughters kept the market open for another fifteen years, and it was still a local gem when the work finally caught up with Fern. She sold the market and enjoyed her days with her family. Of course, her birthday was still the pinnacle of the year, and the large Kennedy Clan would come together each year for the celebration.

The Absecon market remained profitable under the care of Lenny and his wife Betty. The stories from their days spent selling to shore traffic are truly hilarious. Almost everyone who knew Lenny remembers his troublemaking, but the toweringly large man was also devoted to his family. Lenny passed from this world in July of 2009. He departed as a man dedicated to his family and God. Eventually, the market on the White Horse Pike was closed, and another location of Kennedy memories was adrift.

The Bayside Farm Market was another site that proved location is the key to success. It seems the Kennedys were always linked to that other New Jersey trademark: the Shore. Jimmy and Darlene shared their produce with the area for a long time, but after thirty years, they retired to the Lake of the Ozarks in Missouri. Jimmy McIntire embraced Missouri enthusiastically. He hunted for whitetail, fished the Ozarks, and spent lovely years with Darlene. Their door was always open to family, and they often visited New Jersey—the state that held most of their memories. Jimmy passed away in December of 2015. Darlene still lives in Missouri, and from what I gathered from our interview, she is grateful to have married a man who shared her love for hard work, family, and farming. Their son still lives on the property where the Bayside Farm Market once stood, and the big grey barn is still visible for those passing through Leeds Point. Darlene’s prized accomplishment is the work ethic she has passed down to her children. Her children ensure the Kennedy tradition lives on by teaching the same lesson to their own youngsters.

The fortune of Farm Lot 887 is a happy one. It may have been the site of animosity and anger and disappointment, but it was also the site of life, growth, and home. The Kennedy history is fascinating, and even if they were not the influential community members that they were, the stories that sprouted from this land should still be remembered. This research also produced every deed holder for Lot 887, and the list goes back to 1889. I procured a scarce amount of research on each of these deed holders; and already, it is clear there is more history to be uncovered. For example, the first married couple to buy the lot from Galloway Township was Gustave and Marie Gehring. They appear to have been wealthy socialites from Philadelphia who had a propensity for dinner parties and buying New Jersey real estate. Was this their country home? Was Stockton University’s campus the location of Spring dinner parties held by Philadelphia’s rich couples in a bygone time? These questions are important. Our history is important.

I believe the Kennedys have made amends with Stockton, but there are a few who will never forgive the state for claiming their home, livelihood, and memories. Still, the fate of the Kennedy family has been intertwined with Stockton University for decades. It began with Leonard and Fern but was followed by Jimmy McIntire’s years as an employee. Then, daughter Fern married Stephen Brown who also earned a job at Stockton University in the Carpenter’s Shop. He was one of the members of the Cedar Bog Bridge reconstruction project—a place the Stockton community cherishes. Stephen and Fern’s daughter Sara is now a Stockton alumna. Leonard and Fern’s fourth daughter Sharon even attended Stockton later in life—apparently, she was given a load of trouble for this move! In any case, the Kennedy Clan’s memory is alive and still growing. Furthermore, our campus is still ripe for research. Hopefully, these memories never leave our campus: hopefully, Leonard and Fern never wholly leave their home.