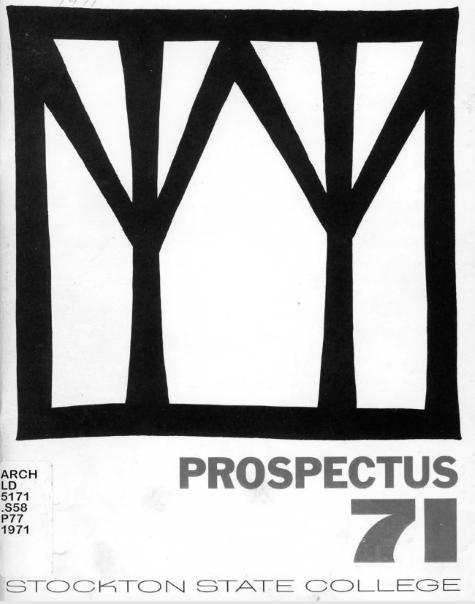

Prospectus 71

By Ken Tompkins

See a complete scan of the original Prospectus 71 here.

How to Begin?

It was not immediately obvious to those of us who started the college how to do it. None of us had had the experience before. So, we followed the usual advice and broke the process down into smaller parts. For example, how would we hire faculty? Would we take as an example any state university and simply replicate the disciplines they had? Would we have someone to teach physics? To teach English literature? To teach psychology? Or any of the other common disciplines?

Surely, we quickly understood, that the College could not offer every discipline. So, which would we cut? There were, we understood, thousands of such questions. Where would the faculty offices be? How would we register students for their classes (keep in mind that this was 1970 and that there were no desktop computers, no easy access to processing and no networks across the college buildings)? Where would the bookstore be located? Would we have a library and would it be sufficient for a starting college? What would the classrooms be like? Would they be equipped with a blackboard? How would we recruit faculty? Where would we put ads so prospective faculty would see them?

In an established college, students arrive and move their belongings to their rooms. They might meet with an advisor whose signature might be required to register. Or, they might simply go through registration picking the courses they want and the times they want and be ready for the first class on the first day. Today, all of this can be done on an iPhone and students can go home for the weekend.

We started with a blank slate and invented the process as we went along.

What was true for the first deans—I was the first dean of General Studies—was true for all of the other people involved with inventing a college. Finance had to face similar problems. Student affairs faced its issues. The higher administration struggled as we did to put in place policies that would lead to the successful education of our students. Plant management had to make sure that the vehicles in the fleet were ready for use. Everyone built from the ground up.

Indeed, our buildings were not ready when we opened and we were forced to change the site to a derelict Hotel in Atlantic City. So, even the best-laid plans can go astray.

It might seem that no one had considered these issues before July 6, 1970, when the deans, and others, began their work. Actually, the process had begun in mid-June of 1970. The results of that initial planning process is what this essay is about.

The first description of what was being done to advance the College’s future is found in a report to the Board of Trustees written on June 1, 1970, and presented on June 10.

We presently are working with a public relations firm on a consulting basis to assist us in creating a “graphic image” for the college. At the moment this means such things as a letterhead, a general information folder, a map, and plans for a bulletin suitable for use by prospective students and counselors. This activity is in the very early stages, but first contacts have been encouraging. We can listen to the complaints when the letterhead and logo actually appear. Then what you suspect about our artistic judgment will probably be confirmed. We do find an increasing need for general information publications about the college and we anticipate that the demand will increase very rapidly. Therefore, we’re trying to get a publications program put together by early summer.

It is clear that the Publications Committee was in full mode in the middle of June

1970.

The First Outline

The College

The Educational Program

Student Life

Note for the Prospective Student

College Roster

Each of these topics had detailed outlines covering every aspect that students and the general public would want to know. The finished Prospectus 71 adhered closely to this outline.

From Outline to The Prospectus

Here is the Table of Contents of the completed Prospectus 71. I intend to discuss the first three sections.

Table of contents

From the president – 5

Aims of the college – 7

Academic programs – 9; College calendar, 10; Academic advising, 11; degrees and requirements, 12; General and liberal studies, 13; Academic organization, 24, major concentrations, 14; Academic organization, 24.

Student life – 29; College governance, 29; co- curricular activities and programs, 30; residential styles, 30; off-campus life, 31.

College staff – 33

The College – 37

Stockton state college board of trustees – 39

New Jersey board of higher education – 41

Accreditation – 42

Campus development – 42

The college and community – 43

Notes for the prospective student – 44; admissions requirements, 44; early admission, 45; part-time study opportunities, 46; programs available in 1971- 72, 46; applying for admission 47; Financial information, 47; Financial aid, 48; housing for students, 49.

College location – 51.

The President’s Message

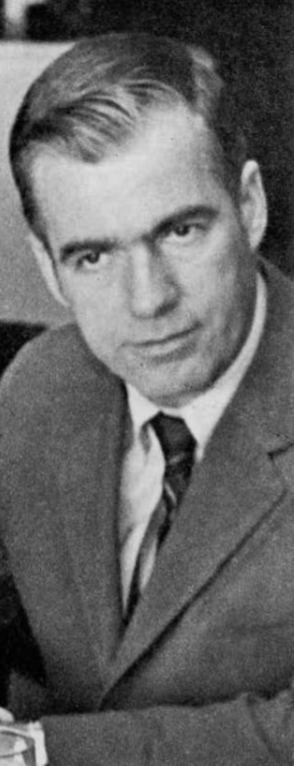

Richard Bjork, the first President, argues that “increased freedom for the individual is what college is about.” But, he notes, “We seldom seem to examine how much what we are doing really produces freedom of the mind, or spirit, or person.”

But, he continues, “at Stockton the pursuit of freedom is real and constant. The pursuit is not a reckless, selfish dash to self-satisfaction – not a simple banquet of simple pleasures. To keep chaos from passing as freedom, or to avoid freedom becoming a disguise for personal tyranny, Stockton imposes a heavy responsibility on all for living with the consequences of freedom. . . . Each person will face the tough demands putting himself to work as a learner.”

Given the fact that this was written in 1970, these words are threateningly clear. The gauntlet was laid down. Stockton would not follow the path of other places where “sex, drugs and rock-n-roll” dominated. This is the “disguise for personal tyranny.” Stockton was not going to be a place where students used their freedom to live lives without consequence. One thinks of Berkeley and Kent State.

The President continues, “if all of us must assume responsibilities for increasing freedom and reaping its benefits, then we quickly face the problems of choice. Freedom confronts us with rapidly growing choices – growing in numbers, complexity, and seriousness. Many turn away from this experience in confrontation bewildered, appalled, or even willing to throw away freedom for any form of order which relieves them of the responsibilities of choices and living with the consequences.”

Choice, or better, informed choices, is the way that unbridled freedom can be channeled to useful ends. Bjork concludes with this paragraph, “Securing freedom depends on knowing what its benefits are and why you must have them. Freedom and purpose stand at the center of what we are doing. Everyone who is a part of Stockton carries continuing responsibility to know what he seeks, to impose that discipline on himself sufficient to achieve what is crucial among the things he seeks, and to reexamine constantly the value of what he seeks.”

All of this recognizes that a student coming to Stockton will be faced with almost endless choices. If a new student wanders into the area where those clubs, fraternities, and sororities have set up their resplendent tables to eagerly engage passersby, how is she to make the choices that may have results for the next years or, even, her life?

The answer, at least for early Stockton, was found in a cooperative and conjoined relationship between faculty and student.

At this point, it is necessary to digress into the many essays on Stockton’s General Studies and Preceptors. Wes Tilley, the first Vice-President of Academic Affairs, had written about a special relationship between a faculty preceptor and Stockton’s first class of students.

Tilley clearly understood that faculty should not be merely signatories to student choices of classes and academic activities. This was the basic requirement across higher education in the late 1960s and early 1970s. For example, as a student, I had been advised in such a system. I was an English major with a Physics faculty advisor! There was no real advice about which course to take or when to take it because there was NO choice. Advising consisted of waiting with others outside the professor’s office, taking a place inside his office, reading down a list which specified which courses to take – determined by which group I belonged to (freshman, sophomore, etc.). Those classes were checked and I took the form to a bursar to pay. NO discussion, NO choice.

Tilley, on the other hand, envisioned an enduring relationship with students which would seriously question a student’s course choices and what those choices would allow in future choices. This dialogue was to be rigorous, careful, deliberate and, most of all, supportive.

A student, then, would come to an appointment at his Preceptor’s office. The Preceptor might start the discussion by asking what career the student wanted to pursue? The student might respond by saying she wanted to be a physician. The Preceptor might then ask whether the student had had success in science courses in high school? On the answers to these, and other questions the Preceptor might suggest an entry Biology course. This Socratic exchange would lead to informed choices on the student’s part, satisfaction on the Preceptor’s part, and a supportive understanding for both.

It is for these reasons that Bjork argues about freedom and choice in his opening

essay in Prospectus 71.

Aims of the College

The text continues to outline three foci of the new College. This section opens with this quotation:

The long-praised claims for diversity and individuality in American higher education begin to sound slightly hollow. Stockton seeks to challenge the trend toward uniformity by renewing or strengthening the capacity of individuals to respond with new skills and attitudes to mounting human problems. The key may well be the individual’s ability to understand stand what resources he already has, what he must acquire, and how he can use these resources in a rational way to turn individual benefits into general, human benefits.

Focus on the college as community

There has always been a strong emphasis on the community at Stockton. It starts with the community of students and Preceptors. There was also a community of the whole College. This was especially true for the very first classes held in the Mayflower Hotel – a derelict building in Atlantic City. All of us who were there were marked as pioneers because we shared the good and the bad of that one-term experience.

The Prospectus states: “Working as a community facilitates the learning of all. Every effort will be made to maintain formal and informal relations among students, staff, and friends of the college which extend everyone's chances to learn. Students at Stockton will find an atmosphere in which social, cultural, recreational, and “class” activities co-mingle. Part of their responsibility is to strengthen this atmosphere.” Perhaps, the largest and most inclusive student activity at Stockton and with the wider community is the work or 1000 students on Martin Luther King Jr. day. Their efforts across Atlantic City and Atlantic County are legion.

Focus on environmental studies

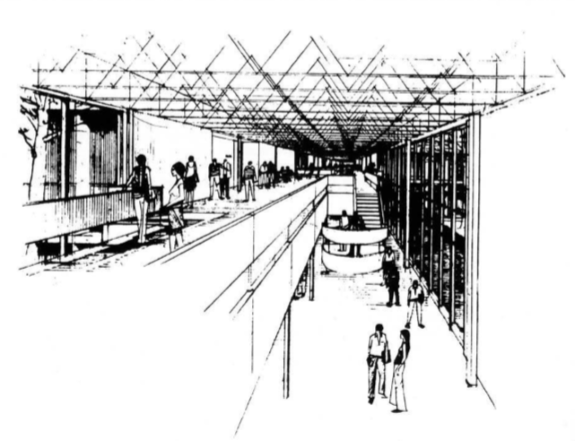

“The college has a unique combination of resources in its own in neighboring physical and human environments. The “pine barren” ecology of the campus, nearby marshlands and marine tidelands provide bases for serious work in marine sciences and environmental studies. Students and faculty may consider what a virtually undisturbed natural environment is like before exploring new designs for its rational and controlled development.”

The University stands on 1600 acres of pinelands. Its Environmental Sciences and Marine Sciences were among the first such undergraduate degree programs in the US. There are today plenty of internships, work-study and seminars in both programs. Finally, the Stockton Action Volunteers for the Environment (SAVE) club was first in the State and may still be the largest environmental student club in New Jersey.

Focus on innovation and experimentation

The third and last “aim” of the new College is described as follows: “Educated men and women must be capable of evaluating the effects of technology on change and understanding how public and private decisions affect such change. Once these dimensions of life are in hand, one has found the first openings to managing those things he creates, and those forces he sets in motion.”

It continues: “The college’s posture of innovation and experimentation is aimed at finding and using more effective and efficient approaches to learning. Strong emphasis will be placed on individualized learning and research including opportunities for students to set their own rates of progress and levels of accomplishment. All the steps taken to support individual learning will face the test of effectiveness since increasing the individual’s power to learn is central to what happens at Stockton.”

The Prospectus is correct. Learning should have been evaluated from the first day of classes. Unfortunately, it wasn’t and evaluation was my responsibility. When I interviewed for a position at Stockton, I was offered one of two positions: General Studies or Arts and Humanities. I chose the former.

Naming things at Stockton kept changing through the early planning phase (i.e., 1970 – 1971). While I interviewed as the Dean of General Studies, when I arrived, I was the Chairman of General Studies. We all bristled at this change because in academia Chairpersons are generally lower in rank than deans.

An amusing story and one that reveals the quality of the rules we lived by has to

do with Dictaphones. By the Fall of 1970 we began to search for faculty candidates.

We sent out advertisements to leading journals read by academicians. Shortly after,

applications poured in. Indeed, we received 5300 applications for 55 faculty positions.

Faced with this workload we requested Dictaphones from the state. Our request was

turned down because in the State’s hierarchy, only deans could have Dictaphones. Stockton’s

response to this silliness was to change our titles to Deans.

About the same time – the fall of 1970 – my deanship was changed from being Dean of General Studies to the Dean of Experimental and General Studies. With that change I was considered the person who would begin to evaluate learning at the college.

In some defense, I was overwhelmingly involved with running a new Division and hiring additional faculty for 1972. This shifted the importance of evaluation of courses downward.

When my six faculty arrived during the summer of 1971, we created five programs: Teacher Development, Methods of Inquiry, Sociology of Sport, History and Philosophy of Science, African-American Studies. I had planned to evaluate Teacher Development and Methods of Inquiry. I decided to delay a review of these experimental courses until they were taught for a few terms to stabilize them. That review never happened because I was “reorganized” (administrative talk for being fired) in 1973.

My sense is that very few courses at Stockton were ever evaluated using scientific techniques of review.

Conclusion

Prospectus 71 continues with more precise information: A Possible Student Program, A Possible Student Program For Those Who Transfer, Academic Organization, College Governance, Admission Requirements, Financial Aid, etc.

The Prospectus was mailed to prospective students, high school counselors and faculty candidates. Indeed, many faculty candidates mentioned how important the volume was when they made their decisions to apply.

It is a remarkable document. It was created by a few staff, about a college that didn’t exist, listing courses that had never been taught, in classrooms that had yet to be built, on a campus that had not be cleared for an audience that had not been seen.

Postscript

Lost in the past 50 years was the knowledge of who created the Prospectus and who created the logo on the front. Research I completed while writing this essay has answered these questions.

The first mention of some sort of descriptive catalog comes in a June 1, 1970, memo meant for the Trustees (quoted above). The public relations firm was the Mark Forrest Agency in Vineland, New Jersey. It had been suggested to the administration by Magda Leuchter, a member of the Board of Trustees. Actually, the firm was a two-man operation – Mark Forrest and William Snyder. It was the latter who created the book. He was in charge of the design of the Prospectus, copy editing the text, taking the photographs, choosing the font, etc. During a phone conversation with me, Mr. Snyder said that the logo was designed by an artist named Apgar though he couldn’t recall his first name. The tall, central figures are trees, according to Mr. Snyder, and not people as has been proposed.

The Prospectus 71, the first of several annual college guides, provides an intriguing view of what early planners intended for Stockton. Current students, faculty, and staff will have their own views of the ways Stockton has remained true to this initial vision.