How Dick Bjork and the Mayflower’s Mickey Finn Room created the Stockton Federation of Teachers

By Tony Marino

When the 55 members of Stockton’s charter faculty gathered at the Mayflower Hotel on the Atlantic City Boardwalk in September 1971 the creation of a militant faculty union at the new college was about as likely as the Phillies winning the National League Pennant that month. (They didn’t. The Phillies finished sixth in the NL East in 1971 with a 67 – 95 record.)

Yet just nine months later in June of 1972 as the college’s first academic year came to a close, 35 of the original 55 faculty signed the Charter that created the Stockton Federation of College Teachers, Local 2275 of the American Federation of Teachers, AFL-CIO (Henceforth referred to as the SFT).

Why? Many factors were involved. But the most important catalyst according to many was college president Dick Bjork. Perhaps the second most important contributor was the cozy confines of the Mayflower Hotel’s Mickey Finn Room. As a result of many informal discussions and faculty meetings that took place in that room, faculty reluctantly concluded that this new college was not likely to become the academic Utopia by the Sea suggested by its main recruiting document, Prospectus 71.

Ken Tompkins, one of the original deans, has an article about this first Prospectus in the “Stockton Stories” section of the 50th Anniversary link on the Stockton University website. He discusses the goals President Bjork outlined in this intriguing document, particularly the focus on the college becoming a self-governing community that would stress environmental studies, academic innovation, classroom experimentation, and evaluation of the results. (Ken provides a link to the entire 50+ page publication.)

He notes that it was designed to be a recruiting document.

“The Prospectus was mailed to prospective students, high school counselors and faculty candidates. Indeed, many faculty candidates mentioned how important the volume was when they made their decisions to apply.“

Prospectus 71 proved to be a fine marketing tool; 5,300 individuals ultimately applied for the 55 faculty positions available at the college temporarily housed for its first semester at the rather dingy, long past its prime Mayflower Hotel on Atlantic City’s famed Boardwalk at Tennessee Avenue. One of its more interesting attractions (loosely applying that term) was the Mickey Finn Room, the former hotel’s bar and lounge converted into a meeting room and general hangout area between classes for students, staff, and faculty.

It also morphed quickly into a makeshift cafeteria sans food service where the college community could consume a bag lunch brought from home or purchased out on the Boardwalk at a nearby cholesterol-generating eatery grateful to have some business as the resort’s traditional summer season waned into fall.

According to Wikipedia, the room’s namesake, Michael “Mickey” Finn, gained fame in the 1890s as a Chicago bar owner who spiked the drinks of unsuspecting patrons and while they were in a stupor had associates drag them out to the alley to rob them. Thus was born the term “slipping them a Mickey.” More about this later.

Notwithstanding the exciting game plan outlined in Prospectus 71 for developing an experimental college, President Bjork from the outset seemed intent only on emphasizing at every opportunity the “evaluation of results” component to the near exclusion of all other goals mentioned in the Prospectus.

In many settings he could be easygoing, charming, even cheery. But from the start, every time he stood formally in front of faculty he soberly reminded us that “Stockton will allow you to try new things but you must be prepared to be judged on the success of your efforts.” And he always made clear he would be the guy wielding the gavel.

His straight-forward “just the facts Ma’am” approach of television detective Joe Friday suggested we should accept reality: we were employed by an institution that the Legislature had already determined before our arrival was just one college among eight in a collective bargaining unit.

Actually, few of the 55 faculty recruits had personally met President Bjork when interviewed the previous Spring or early Summer. The deans and and in some interviews Academic Affairs Vice President Wes Tilley were the friendly (and sincerely) enthusiastic marketeers of Stockton’s experimental classroom possibilities and its goal of becoming an inclusive academic community. No one volunteered information about a mundane thing like a “bargaining unit.”

Once exposed to President Bjork’s stark message it began to occur to many of us that

perhaps Prospectus 71 and the upbeat presentations by the deans during our interviews were tantamount to

being slipped a Mickey of unachievable academic promises.

An interesting event soon underscored the reality of our new environment. On a sunny

late summer day academic activities were suspended and all faculty and staff were

asked to mosey on down the Boardwalk to the Convention Center to hear welcoming speeches

by President Bjork, Trustees, and State Senator Frank “Hap” Farley—who happened to

be in a tight re-election race he subsequently lost in November. In his speech Farley

was effusive in his praise of the new college. He also effusively praised himself

for being the legislative force in creating it.

Afterwards, as we trekked back up the Boardwalk to the Mayflower a group of us discussed

the senator’s speech and Farley’s reference (probably quite accurate) to his influential

role in creating this new college. Was Farley’s latent message that “his” college

was now the source of our employment and that we were expected to demonstrate our

appreciation in the upcoming election?

A second event drove home the disconnect between creating an experimental college

in a South Jersey environment that was a totally different world than our 1960s free-wheeling

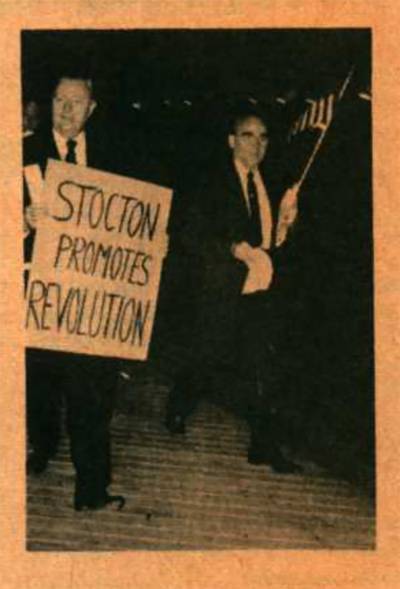

University experiences. In late October a group of evangelical Christians led by Cape

May’s nationally known ultra-conservative radio personality Reverend Carl McIntire

marched on the Boardwalk outside the Mayflower holding signs protesting the community

lecture series by political science Professor Bill Daly titled “Revolution and the

Revolutionary.” (Photo below)

Daly’s actual message in his lecture series was hardly that of a wild eyed, radical professor’s endorsement of Revolution. Instead, the lectures were a serious academic exercise exploring the taxonomy of revolutions and the background of revolutionaries. There was no evidence that Reverend McIntire or any of his fellow protestors heard anything actually said by Daly (they never left the Boardwalk). However, just daring to talk in public about communism plus their concern over the college’s strange logo, which supposedly suggested devil worship, was sufficient motivation to express their outrage and wave American flags on the Boardwalk at Stocton (sic )State College’s main entrance of the Mayflower Hotel.

These two events, President Bjork’s constant buzz-killing barrage of dour warnings about evaluating all members of our college community against standards he alone would establish, and the fact that Stockton was but one of two (Ramapo was the other) new members of an existing state college collective bargaining unit gave faculty issues to contemplate over lunch and in subsequent meetings in the Mickey Finn Room.

As the first semester progressed through October, November, and December, the room

often hosted meetings of two key components of the Stockton shared governance experiment:

Collegium and College Council. Unfortunately, both withered away in relatively short

order in large part because neither proved for structural reasons (a/k/a Dick Bjork)

capable of solving any issues other than naming the school’s mascot. (See postscript

at the end of this article.)

As Stockton’s first semester neared its end, the Mickey Finn Room hosted a different

series of meetings—the recruitment presentations by representatives of the three organizations

contesting the right to represent faculty, librarians, and certain staff members in

collective bargaining negations with the state.

The New Jersey Educational Association (NJEA) at that time held bargaining rights for the preexisting six state colleges and many county colleges. The American Association of University Professors (AAUP) represented faculty at Rutgers. The American Federation of Teachers (AFT) was at that time a powerful, militant presence in the K-12 system of Newark and neighboring New York City. The AFT, unlike the NJEA and AAUP, had no problem calling itself a union and was proud to be associated with the blue collar AFL-CIO state and national labor union movement.

I perhaps oversimplify because many issues were indeed in play, but after first contact the NJEA was seen by many of us as controlled by its K-12 bargaining units while the AAUP seemed to regard the state college system as an afterthought to its main focus, Rutgers University.

The AFT representatives at their first visit to the Mickey Finn Room pitched a straight-forward, plausible message. “Based on what you have told us,” they said, “this Bjork guy, despite all the initial talk of shared governance, has shown he wants to call all the shots and the state legislature has armed him with the ammunition to do so with impunity—unless you vote to be represented by a “real” union that won’t let him get away with it!”

And thus was born (unofficially) the Stockton Federation of Teachers.

In January we abandoned the Mayflower and its Mickey Finn Room and moved to the Galloway campus. From then until the June signing of the charter that actually created the SFT as a unit within the Council of New Jersey State College Locals (CNJSCL), AFT, additional events occurred that solidified union support by 35 of the 55 member initial cohort of Stockton faculty.

The officers were Tom Wirth, President (NAMS-chemistry), Lee Loft, Treasurer (ARHU-languages), and John Miller, Secretary (ARHU-languages). Executive Committee members were Ralph Bean (NAMS-math), William Gilmore (ARHU-history), Anthony Marino (SOBL-sociology), Elizabeth Marsh (NAMS-environmental studies), and Ralph Smalley (SOBL-Urban Studies.)

Organizing continued at Stockton and the other seven state colleges during the fall semester of our second academic year. In the spring semester, February 1973, the CNJSCL ousted the NJEA as the statewide bargaining agent for all eight state colleges by a single vote in a total bargaining unit of nearly 3,000 eligible voters that year.

Why? Mostly because of strong and effective SFT leaders and continuous active membership participation during the last half century that began in the environment created in the fall of 1971 by Dick Bjork and spawned in the Mickey Finn Room of the long-gone Mayflower Hotel.

The Stockton faculty, librarians, and eligible staff that voted in that election in February 1973 went 99 to 1 for the AFT. The SFT was then and still is today, nearly 50 years later, among the 11 locals that currently comprise the CNJSCL the campus union with the highest percentage of active membership.

Postscript: For more background on the early Stockton I again refer the reader to Ken Tompkin’s Prospectus 71 article mentioned above. The Reaching 40 book about Stockton edited by Ken Tompkins and Robert Gregg (2011) has an excellent article by John Searight on the SFT’s early years titled “The Union Made us Strong.” Other articles in the Reaching 40 volume that touch upon the issues discussed above include “Breaking Eggs—Richard Bjork” by Robert Gregg, “The Stockton Idea,” by William Daly, and Robert Helsabeck ‘s “Shared Governance.”